Durham is a city founded on a traffic accident.

It’s the year 995 AD, and Saint Cuthbert of Northumbria is heading towards Chester-le-Street in an attempt to escape Viking raiders. It’s possible he’s travelling on a wagon, or maybe perched on a plank of wood hefted onto the shoulders of his followers. Nothing comfortable, anyway – but that wouldn’t have concerned Cuthbert much, since at that point he’d been dead for 308 years.

At some point, the procession comes to a halt. If it’s using a wagon, the wheel might have got stuck; if Cuthbert was on a bier, maybe sore shoulders were the reason. His previous resting place, the holy but increasingly Norse-plundered island of Lindesfarne, was far behind him in time and space – and his future was uncertain. The monks carrying him had roamed to and fro, settling in nearby towns for a time but ever driven onwards in search of a fitting (and easily-defended) resting place for their sacred charge…

Now they’re somewhere near Warden Law, and Cuthbert refuses to go any further. More specifically, his coffin won’t. The entire congregation puts their shoulders into it – but it won’t move. It’s a sign! They all decide to stay put for a few days, fasting and praying in the hope that Cuthbert explains his reluctance to continue. Sure enough, the saint appears in a dream and points them towards “Dunholm”.

Apart from translating as island hill, this name meant nothing to anyone present – until they stumbled on a milkmaid searching for her “dun cow” (a very common element in early English folklore), and following her, they discovered the island upon which Durham now stands, and built a church to house the saint and his Lindesfarne relics.

In a purely strategic sense, it’s a magnificent location. The river curls round it on three sides, and the island is high enough to spot any intruders long before they’d arrive. Of course, the legend says it wasn’t their decision, it was Cuthbert’s – but they must have been even more easily persuaded when they clapped eyes on the place….

It’s a lovely story. Only the most leaden-hearted historian would want to challenge it – but it’s too good a location to assume it was left untouched for the whole of prehistory, and in fact it wasn’t. There’s archaeological evidence of local settlements stretching back to 2,000 BC. There’s no way they would have missed this natural fortress. Yet it’s true that the modern city owes its existence to some part of Cuthbert’s story. How much? That’s for a higher power to answer.

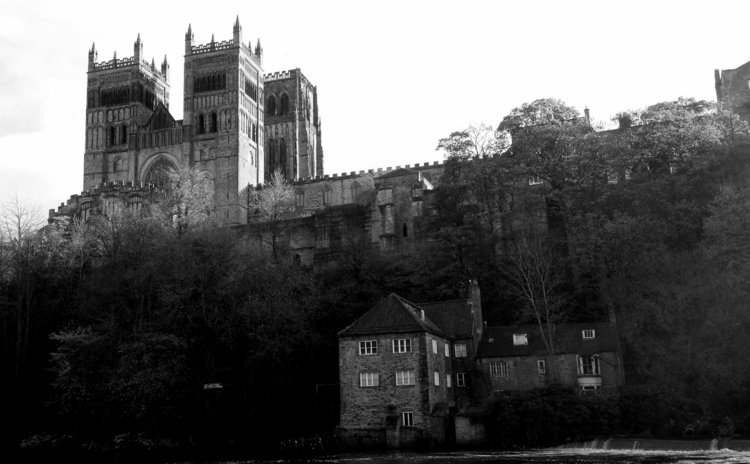

As for Cuthbert’s supernatural slamming-on of the brakes – I have another theory. As far as I know, nothing is recorded about what time of year all this took place – and here’s what Durham looked like a few days ago, on a particularly savage December day:

It’s a terrible thing when you put your sacred possessions down for a bit so you can stretch your shoulders – and then discover they’ve frozen to the ground.

(Maybe.)

This series (where I’m visiting every city in the UK and Ireland) is about two things: stories and patterns. I’m working under the perhaps unfashionable assumption that everywhere is fascinating and unique if you look hard enough (ie. it has a story) – and yet there are common rules for how cities are born and how they grow, rules that can be learnt, and then applied to your own backyard so you can understand where you live a bit better.

Durham’s a fascinating example of those principles at odds with each other. A natural defensive point? Yes, but – the Cuthbert thing. Okay, but beyond that, are the city’s saintly origins an entertaining irrelevance when it comes to political reality, a doodle in the margins of the city’s history?

Here’s the answer, in the form of a shameless but accurate bit of bragging from the steward of one of Durham’s medieval bishops:

There are two kings in England – namely the Lord King of England wearing a crown in sign of his regality, and the Lord Bishop of Durham wearing a mitre in place of a crown in sign of his regality in the diocese of Durham.

What defines the power of a king? You could argue about families and noble blood, but in a practical sense it always comes down to money and the sword. It’s about taxation, land, trade, and the ability to mobilise troops when the situation calls for it. And in all these ways, Durham’s “prince bishops” had the God-appointed ability to act like royalty. They minted their own coins, they set their own laws (via their own parliament), they entered into negotiations with Scotland, they granted trading charters for markets and towns – and they raised their own armies. In every sense that mattered, they were kings in the North for centuries.

From 1071 to 1836, the Prince Bishops (our term for them, not theirs) consolidated their extraordinary power around Durham Castle (pictured). Nowadays you’ll see students trudging in and out of it – it’s the home of the city’s University College, one of the city’s 14 colleges with the main university campus located a few miles south. I pity students who start their journey into the brutal world of post-academic employment in a castle. Talk about setting unrealistic expectations.

(Fun fact: for upwards of £40 a night, non-students like you and I can also stay within the castle’s walls, breakfast included. “Live like the divinely-appointed somewhat-equivalent of a king!”)

![20151112_153313-01[1]](https://i0.wp.com/feveredmutterings.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/20151112_153313-011.jpg?resize=750%2C508&ssl=1)

But it’s not the castle that first catches the eye of the modern visitor.

The Cathedral Church of Christ, Blessed Mary the Virgin and St Cuthbert of Durham – better known as Durham Cathedral – is looking its age. I studied and worked in nearby York for 12 years, and walked past its cathedral every day for years. York Minster is pristine and beautiful, glowing gold in the evening light. It also looks a touch…unconvincing, a little too clean to be a thousand years old. Durham Cathedral isn’t like that at all. The battlements facing the river are blackened and scarred from centuries of being assaulted by the weather. It’s handsome, but in a craggy, pitted, deep-lined way.

It’s the first thing you see from the window of your train. It’d be the first sign of the city as you approached by road. It’s both inspiring and terrifying, a warrior-monk, grizzled but non-threatening…

And it says, There Is Real Power Here.

That’s the whole point, of course. From its beginnings as a temporary shrine for Cuthbert and his relics, through various incarnations and additions to the Norman cathedral framework began in 1093, it’s been master of Durham. The city was built around it, to serve it – and if the story can be believed, it all goes back to Cuthbert’s bier, or wagon, stuck on the road.

It’s a tough thing keeping a thousand year old cathedral in one piece. York Minster now charges for entry (something a number of people aren’t too happy about) and other cathedrals around the UK are taking a similar route to funding their repair-work. Durham isn’t. It’s free access for all – although they’d love it if you made a donation. Problem is, most people don’t. It’s a World Heritage site that gets nearly three-quarters of a million visitors a year, and of course it’s a working place of worship. That’s plenty of expensive wear and tear. Where does the money to fix it come from?

Enter something called Open Treasure. The cathedral’s innermost recesses are being cracked open and redeveloped into a series of exhibitions that tell the shrine of Cuthbert’s (and by extension Durham’s) origin story. As part of the Lumiere media coverage, I had a tour of the spaces they’re reworking – the Monk’s Dormitory, the Refectory Library, the Great Kitchen. These are vast spaces, the kind that give you a crick in your neck. It’s astonishing to think of them being left behind lock and key, just gathering dust – but, not for much longer.

The current phase of work (costing £10.5 million) is due to be completed sometime in 2016, and it should be an incredible sight. It’ll also be a beautiful example of putting the fabric of a city’s history back to work, via an admission fee to the new areas.

Cuthbert. The Prince Bishops. The cathedral. These are the keys to understand how Durham came about. But if you arrive on a sunny day, forget that for a while, and just wander around, feasting your eyes – because Durham is gorgeous.

It’s the best kind of gorgeous, too – not showy, not putting on an act for the tourists, not trying so hard that it forgets to be a place that people actually live.

Although, the statue commemorating the Durham Light Infantry look a little like it’s showing off. Just a bit.

It’s a fine city with an unusually fine story behind it.

Just pick a nice day to go, ok?

Getting There

I caught the train heading towards Newcastle – Durham’s on the East Coast main line from London, 45 minutes north of York and midway along the famous Stockton-Darlington railway, the very first in the world to carry passengers. Ticket prices range from “Yeah Okay” to “WHAT?” (Make sure you know how to buy cheap train tickets in this country.)

Anyway, that’s the simplest way I’ve found, other than just walking there like a modern Cuthbert-bearer. No Megabus, alas: your best bet is getting to Newcastle and catching a local bus like this one.

I was in Durham covering Lumiere for Must Love Festivals, supported by Lumiere itself, Artichoke, Visit County Durham and Visit Britain. I was also supported by really thick gloves and a nice scarf. I should have worn a hat.